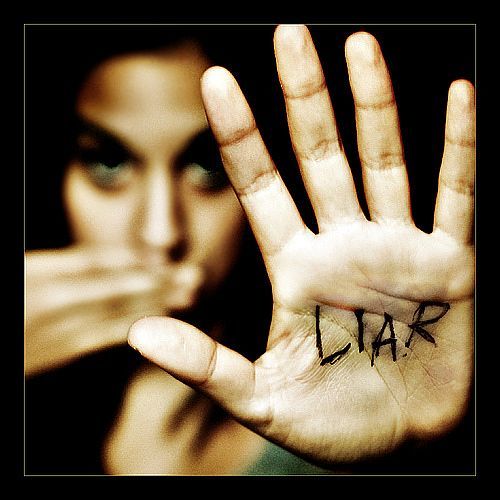

Inside the

Mind of a Liar

Greg Parker

My experience with a pathological liar began following high school, with a girl I had been dating (I’m realizing a lot of my stories start this way). She was a

quirky, fun-loving girl that always had a story to tell, sometimes too good of

a story to tell. It started off with

interesting "facts" about her life, like how she spent a summer studying ballet

at the Joffrey Ballet School in New York City.

She could even stand on her toes to prove this to me. This was all believable enough, until she

elaborated with stories of forced pirouettes and near starvation by the

instructors. The final lie was about her

twin brother (Chris I think) who supposedly died in a fire, but her parents had

dealt with this loss by destroying all evidence of him and not mentioning his

name. She looked directly at me, and

said, “Don’t ever ask about Chris.”

What causes this need to lie? We all have seen people that always seem to

have a great story, the one-uppers or story hoarders. They take the attention away from your mundane

story, and destroy it with a better one.

One reason people lie is the result of the cost-benefit ratio. Many people see very little cost to their

lie, but a possible huge benefit. These

benefits include better social standing, more respect, more opportunities, and higher

quality mate. There seems to be two categories of liars, those who lie a little (most people), and those who lie a lot (the rest).

Cheating Experiment

In his book, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, Dan Ariely talks about his favorite experiment involving liars. In this experiment, they gave a group of people a set of 20 math questions and five minutes to complete as many as possible. They say they will give them one dollar for every question finished. At the end of the five minutes, they are asked to first shred the paper in the back of the room, then walk to the front and report the number they finished, and are then paid. What the group doesn't know is the shredder only shreds the borders of the page, and researchers can compare the true work done with the reported work done. They found that on average people completed four problems and reported that they completed six. There were a few that reported a lot more, but the vast majority were cheating a little.

Further experiments showed that people were more likely to lie when they received tokens that could be exchanged for money, reporting double the amount of completed questions! This result may reveal how our cashless society may encourage cheaters, like what was seen in the recent financial meltdown of 2008.

Pseudologia fantastica

Pseudologia fantastica is the scientific name for a pathological liar. A clinical diagnosis is comprised of four requirements:

- The stories are not entirely improbable and are often built upon a matrix of truth

- The stories are enduring

- The stories are not told for personal profit per se and have a self-aggrandizing quality

- They are distinct from delusions in that the person when confronted with facts can acknowledge these falsehoods.

There doesn't seem to be much available in terms of treatment or medication. The best treatment may be early therapy to inform the patient why telling the truth is important, followed with long care treatment and ongoing evaluation. The problem with pseudologia fantastica is that the patient is lying to themselves as well as everyone around them, which they likely accept as truth.

Physiological differences in pathological liars

For years scientists didn't believe that there was any neurological basis to lying, cheating, and manipulative behavior, but these assumptions were untested until 2001 when functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies began. In these studies, researchers looked at an otherwise healthy person, that lies. The fMRI showed increased bilateral activation in the prefrontal cortex while lying.

In 2005, Dr. Yaling Yang of USC decided she wanted to study the structural differences seen in pathological liars compared to non-liars. She found the liars from a group of 108 from five temporary employment agencies in Los Angeles. Out of this group, she found 12 liars, 21 normal controls, and 16 anti-social controls (showing anti-social behavior but not pathological lying). When she performed fMRI on all groups, she found something interesting: liars showed significant increase in prefrontal white matter and slightly reduced gray matter (Fig 1). Also seen is a significant decrease in the prefrontal gray/white matter ratio (Fig 2). Interestingly this is the opposite of a person with autism, which have significantly more gray matter than white matter.

In 2005, Dr. Yaling Yang of USC decided she wanted to study the structural differences seen in pathological liars compared to non-liars. She found the liars from a group of 108 from five temporary employment agencies in Los Angeles. Out of this group, she found 12 liars, 21 normal controls, and 16 anti-social controls (showing anti-social behavior but not pathological lying). When she performed fMRI on all groups, she found something interesting: liars showed significant increase in prefrontal white matter and slightly reduced gray matter (Fig 1). Also seen is a significant decrease in the prefrontal gray/white matter ratio (Fig 2). Interestingly this is the opposite of a person with autism, which have significantly more gray matter than white matter.

White matter is comprised of glial cells and myelinated axons within the central nervous system. It serves as a communication relay between areas within the cerebrum, and between the cerebrum and other parts of the CNS. This increase of white matter seen in liars is thought to increase the speed of communication between various parts of the brain, and may give the person this ability to come up with a convincing lie, quickly. The decreased amounts of gray matter may decrease the ability of the patient to fully understand the consequences of lying.

In 2007, Dr. Yang wrote a short report to update the world of psychiatry of her findings and theories. First, she theorized that a smaller gray/white matter ratio could predispose a person to increased levels of lying. Her second idea, is that when a child is growing, and starts lying due to social pressures, it is conceivable that repeated lying activates the prefrontal circuit underlying lying, and changes the structure of the brain. She finishes by proposing a way to find the truth between these opposing hypothesis- a prospective longitudinal study assessing the amounts of both white and gray matter against the amounts of lying, from childhood to adulthood. Maybe Dr. Yang's research on pathological lying may someday lead to better treatment of this potentially serious condition.

Listen to the podcast on lying: Radiolab

References:

Ariely, Dan, The Honest Truth About Dishonesty, Harper Collins, New York 2012.

Yaling, Y. et al. 2005. Prefrontal white matter in pathological liars, PJ Psych 187:320-325.

Yaling, Y. et al. 2007. Localisation of increased prefrontal white matter in pathological liars, PJ Psych 190:174-175.

Ganis,G.,Kosslyn, and S.M., Stose, S. 2003. Neural correlates of different types of deception: an

fMRI investigation,Cerebral Cortex 13:830-836.

Carper, R. A.,Moses, P., and Tigue, Z.D. 2002. Cerebral lobes in autism: early hyperplasia and abnormal age effects, Neuroimage 16:1038-1051.

Great blog, Greg! And I love how you started it with one of your famous dating stories :)

ReplyDeleteVery interesting that there is a possible anatomical link to lying. I wonder what other behaviors or illnesses may correlate to this