"So, naturalists observe, a flea

Has smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller still to bite ’em;

And so proceed ad infinitum." - Johnathan Swift

In an earlier blog, I discussed some current research in the

field of microbial symbiosis within a human host. However, bacterial symbiosis

is known to be present in a variety of different animals. While attending a physiology lecture by

Professor Emily Taylor at Cal Poly SLO, the role of bacterial symbiosis in a

species of mites was presented, with striking results of this symbiotic

association. The bacterium, in this case of the genus Wolbachia, has been shown to increase the proportion of females in

a population, among other things, due to direct effects on the reproductive

physiology of the mite itself. Upon

hearing that presence of a bacterial species can drastically affect the

physiology of arthropods, I became interested in the role of this bacterium in arthropod

species, and decided to share some current research aiming to characterize the

symbiotic relationship between Wolbachia

and its arthropod hosts.

In a recent paper by Zug and Hammerstein, it is estimated

that the bacterium is present in approximately 40% of terrestrial arthropod

species1. This alarmingly high proportion suggests that

there may be some conferred fitness advantages due to this symbiotic

association. Wolbachia has been

studied extensively for its ability to modulate host reproductive physiology,

inducing large proportions of female progeny in infected individuals through

mechanisms such as cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI). Interestingly, in a review

by Crespi and Schwander, it is suggested that asexuality induced by Wolbachia infections may contribute to

the accumulation of deleterious genetic elements that are normally eliminated

via recombination and other mechanisms exclusive to sexual reproduction2. Why then would there be such

an alarmingly high proportion of arthropod species infected if this symbiosis

is genomically disadvantageous?

A recent study by Xue et al examined the physiological roles

of Wolbachia symbiosis in Bernisia tabaci, otherwise known as the

common whitefly. The role of Wolbachia

symbiosis in whitefly biology is poorly defined, so this study represents the

first of its kind to asses various reproductive and non-reproductive roles of

this particular relationship3. To assess the role of Wolbachia symbiosis, targeted removal of

this organism was achieved using rifampicin. The authors were able to show,

using PCR and other molecular techniques, that this antibiotic could be used to

remove Wolbachia populations without

affecting the presence or abundance of other microbial symbionts of the

whitefly. Whiteflies were separated into two groups, treatment and

control. Within the treatment groups, whiteflies were exposed to rifampicin for

12, 24, 36, or 48 hours. The development

time of F1 progeny hatched from eggs in which the mother was exposed to

rifampicin increased significantly in all time groups. Additionally, the

percent viability of F1 progeny was compared between treatment and control

groups.In the flies where Wolbachia

was removed the viability of their F1 progeny decreased, and tended to decrease

more with longer rifamipicin exposures. These results suggest that Wolbachia presence in the mother before reproduction

confers a strong fitness advantage to those progeny, while the absence of Wolbachia is deleterious to development

time and also survival of new progeny. Also shown previously, this study

reports that there is an increase in the proportion of male progeny as exposure

time to rifamipicin increased. It seems

as though symbiosis is crucial for whitefly fitness, perhaps by providing the

host with some essential non-dietary nutrient, which explains the harsh

reduction in percent survival and growth suppression present in Wolbachia negative flies.

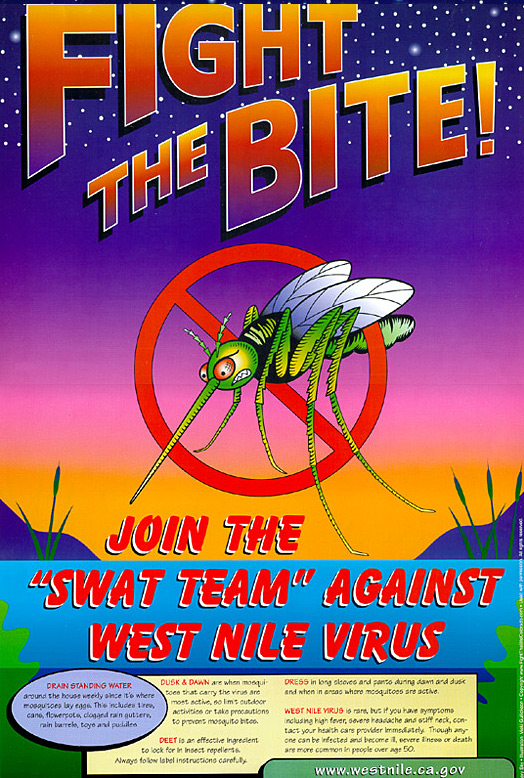

Recently, the biology of this organism has been studied for use as a control strategy for diseases that are commonly transmitted by arthropods, such as malaria and West Nile Virus. Husain et al describe a decreased viral secretion in cultured cells from Aedes aegypti which are infected with Wolbachia5.

While there is a paucity of evidence describing the exact

mechanisms in which Wolbachia exerts

this modulatory effect on its arthropod hosts, there is compelling evidence

that this symbiosis is not only necessary, but beneficial to may organisms,

including ourselves.

References

1. Zug, R. & Hammerstein, P. Still

a host of hosts for Wolbachia: analysis of recent data suggests that 40% of

terrestrial arthropod species are infected. PLoS ONE 7, e38544

(2012).

2. Crespi, B. &

Schwander, T. Asexual evolution: do intragenomic parasites maintain sex? Mol.

Ecol. 21, 3893–3895 (2012).

3. Xue, X. et al.

Inactivation of Wolbachia reveals its biological roles in whitefly host. PLoS

ONE 7, e48148 (2012).

4. Zhang, Y.-K. et al.

Diversity of Wolbachia in Natural Populations of Spider Mites (genus

Tetranychus): Evidence for Complex Infection History and Disequilibrium

Distribution. Microb. Ecol. (2013). doi:10.1007/s00248-013-0198-z

5. Hussain, M. et

al. Effect of Wolbachia on replication of West Nile virus in a mosquito

cell line and adult mosquitoes. J. Virol. 87, 851–858 (2013).

As a general rule, there is certainly a not insignificant rundown of little animals that truly bugs creatures and people alike. Shockingly, they take a few structures and sorts also their techniques and means how they invade people and hairy creatures too. check my blog

ReplyDeleteThese kinds of nets are usually used outdoors in camping and dealing with swarms of mosquitoes. There are nets available to cover any part of the body, or the whole body itself. mosquito netting by the yard

ReplyDelete