A BLOG ABOUT METABOLIC SYNDROME AND CUMULATIVE EFFECTS OF A POOR DIET

Gennarina Riso

|

|

Figure 1. What if we really

looked like what we eat? I might be waddling around like a big container of

peanut butter, or even worse… a big tall beer. (http://www.mmm-online.com/mmm-awards-2011/article/214098/)

|

We’ve all heard the saying

“you are what you eat”. As well educated, young, and reasonably active

individuals, most of us don’t need to worry too much about this – we do eat

fairly healthfully on a daily basis, and even when we don’t, we have the

resources and know-how to better our food choices.

But what about people who

don’t have access to knowledge about nutrition? Since having my job in the ER,

I have thought a lot about how (seemingly) close the correlation is between

having a healthy diet, remaining active, and avoiding chronic illnesses. It

seems to me that most of the cases we see in any given day would be nonissues

if people adopted some serious lifestyle changes. In America, poor diet and

sedentary behavior are of epic proportions. And while it’s no news to us that

being chronically overweight and eating a typically high-fat Western diet contribute

to incidence of Type II Diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure

(just to name a few), the cumulative effects of having a poor diet are much

more convoluted and additive than they appear. But how many people truly

understand what lifestyle choices to make? And further, can they afford to do

so?

In addition, I got to

thinking about how exactly Americans became so unhealthy – what is it about our

society in particular that leads to such overabundance of excess? According to my

research, much of the “spike” in obesity in this country is due to the

increased availability of meat and oil products after World War II (not to

mention plastic and other conveniences). In addition, the concept of “super

sizing” or “economy sizing” (in other words, getting more product for less

money) played greatly into the spike in calorie consumption that took place.

Families who once barely had enough food or resources to survive could now buy

more food than they could ever dream of, so self-control was really not at play

here, and with good reason. In addition, where families once made their own

food from scratch, grew their own vegetables, and owned one family car,

suddenly streamlined products appeared on the market that greatly changed the

dynamics of the American household. Suddenly, America was more focused on

productivity than ever – and while there are thousands of such examples, TV

dinners are particularly symbolic in terms of this topic, as cooking and eating

meals together became less common than heating up a frozen meal in the

microwave and sitting in front of the television.

|

|

Figure 2. An example of a

classic Swanson TV dinner from the 1950’s. Very convenient, but how much

nutritional benefit is there? (http://itthing.com/the-history-of-the-tv-dinner)

|

But what is it exactly about

eating poorly that contributes to such physiological mayhem down the line? And

how is it that our diet can play into our immune function and cause inflammation?

The answer is surprisingly

straightforward, as I learned this quarter in BMED 545. When the endothelial

cells that line our blood vessels become activated (which can happen in

response to turbulent blood flow, or even simply increased blood flow), they

express adhesion molecules that allow monocyte extravasation into the

subendothelial space. They also secrete chemokines (such as MCP-1) that help

activate leukocytes. So, when macrophages are present in the subendothelial

space, they secrete cytotoxic superoxides in order to prevent infection. If

there are high plasma LDL levels, once they filter through the space between

contracted/activated endothelial cells, they react with these superoxides,

which is a very bad situation, as this contributes to the positive feedback

loop that involves more and more immune activation and eventually leads to the

formation of a plaque that contains cholesterol, LDLs, macrophages, and other

immune cells (such as helper T cells, which secrete INF-g, causing macrophages to secrete TNF-a, both

of which are common proinflammatory markers). Obviously plaque formation alone

is dire, but if that plaque ruptures, endothelial cells are exposed to many

combinations of factors that can lead to a blood clot quite easily, most commonly

leading to MI, but also seriously increases risk for stroke and pulmonary

embolism.

|

|

Figure 3. A simple schematic of how eating a

poor diet can lead to coronary heart disease (CHD), just to name one deleterious

side effect.

|

As if all of this isn’t scary enough, research

has shown that increased emotional and psychological stress can promote some of

the oxidative and proinflammatory pathways (even in the absence of physical

injury) that having a high fat diet can – so imagine how dangerous it would be

to be stressed and eat poorly! Because depression is also correlated with poor

sleep patterns, which further increase our risk for infection and immune

response, it is easy to see how this situation could spiral out of control. Janice

Kiecolt-Glaser (2010) cites longitudinal studies that explicitly show that

people who are chronically stressed over a 6 year period have significantly

higher amounts of proinflammatory cytokines circulating through their bodies at

a given time than those without chronic stress. Further, postprandial lipemia

can also increase expression of inflammatory markers, and while the spike in

lipid levels may be short-lived, the positive feedback loop associated with

some of this inflammation could be much longer lasting and cumulative,

especially if a high fat diet is the “norm”. Similar research also indicates

that one single meal high in fats can lead to endothelial cell activation and

increased expression of adhesion molecules that are necessary for the monocyte

extravasation that I mentioned above.

|

|

Figure 4. Even the autonomic nervous system is involved!

Although, that is a subject for another day.

|

Before I begin to talk about some of the ways

we can combat having metabolic syndrome ourselves, I just have to share one

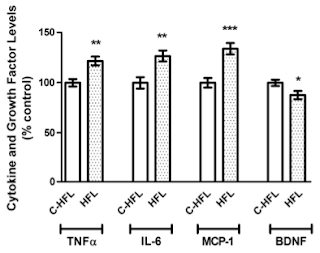

more thing… Pistell et al. (2010) performed fascinating study using a mouse model

that showed that mice who were fed a high fat diet (in particular, a “high lard

diet”) showed cognitive impairment when compared to mice who ate a regular

diet. Further, these same mice were also shown to have significantly higher

levels of proinflammatory markers in their brains (Fig 5)! If that won’t make

you stop hitting up Jack in the Box, I don’t know what will.

|

|

Figure 5. Mice fed a high-fat lard diet showed

significantly higher levels of the above mentioned proinflammatory cytokines

and markers when compared to mice fed a control diet.

|

The good news? As discussed in BIO 502 lab last

week, eating a Mediterranean Diet has been associated with lower instance of

heart disease and many of the pathologies I described above. In 2011, Kastorini

et al. did a metanalysis on 50 past studies involving the Mediterranean Diet

(MD) and metabolic syndrome, and they showed that not only is the MD negatively

associated with metabolic syndrome as a whole, but also with all of its

separate components! Luckily, eating like an Italian is no punishment; all you

have to do is eat a well-balanced diet of fruits, vegetables (flavonoids!),

whole grains, healthy fats (olive oil!) antioxidants (salmon!), and even some

dark chocolate and red wine. They key to adopting the healthy Mediterranean

style is moderation. For example,

studies that show lower instance of heart disease, obesity, inflammation, and

high cholesterol in people who comply with a MD also note that they have a

relatively lower dairy intake than a Western Diet, and the dairy that they do

consume is generally low-fat. After all, we must take into account inflammation

in the animals we consume and how that may manifest in our own bodies. But that

is a subject for another day.

Essentially, the take-home message is that our

grandparents and great-grandparents would have been better off (I will argue)

from a health perspective if they did not change their dietary habits in such a

drastic manner.

|

|

Figure 6. A Mediterranean Food Pyramid. Note

that it gives you information about what you should be consuming on a daily,

weekly, or monthly basis! (http://pikimal.com/diet/vs/dash-diet/mediterranean-diet)

|

Mangiate, bevete e sopratutto divertitevi!

(Eat, drink, and be merry!) In moderation, of course; at least in regards to

the eating and drinking J

|

|

|

References

Pistell, P., C. Morrison, S. Gupta, A. Knight,

J. Keller, D. Ingram, and A. Bruce-Keller. 2010. Cognitive impairment following

high fat diet consumption is associated with brain inflammation. Journal of

Neuroimmunology 219:25 – 32.

Nicklas, B., W. Ambrosius, S. Messier, G.

Miller, B. Penninx, R. Loeser, S. Palla, E. Bleecker, and M. Pahor. 2004. The

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 79:544 – 551.

Giugliano D., A. Ceriello, and K. Esposito.

2006. The effects of diet on inflammation. Journal of the American College of

Cardiology 48:677 – 685.

Esposito, K., and D. Giugliano. 2006. Diet and

inflammation: a link to metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. The European

Heart Journal 27:15 – 20.

Chrysohoou, C., D. Panagiotakos, C. Pitsavos,

U. Das, and C. Stefanadis. 2004. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet attenuates

inflammation and coagulation process in healthy adults. Journal of the American

College of Cardiology 44:152 – 158.

Kastorini, C., H. Milionis, K. Esposito, D.

Giugliano, J. Goudevenos, and D. Panagiotakos. 2011. The effect of

Mediterranean Diet on metabolic syndrome and its components. Journal of the

American College of Cardiology 57:1299 – 1313.

Alberti, K. and J. Shaw. 2005. The metabolic

syndrome – a new worldwide definition. The Lancet 366:1059 – 1062.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. 2010. Stress, food, and

inflammation: psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition at the cutting edge.

Psychosomatic Medicine 72:365 – 369.

Physiological Mayhem! Great post Gennarina

ReplyDelete